The Handwritten Playbill as Cultural Artifact: A French Amateur Theatrical Aboard the British Prison Ship, Crown

Mary Isbell

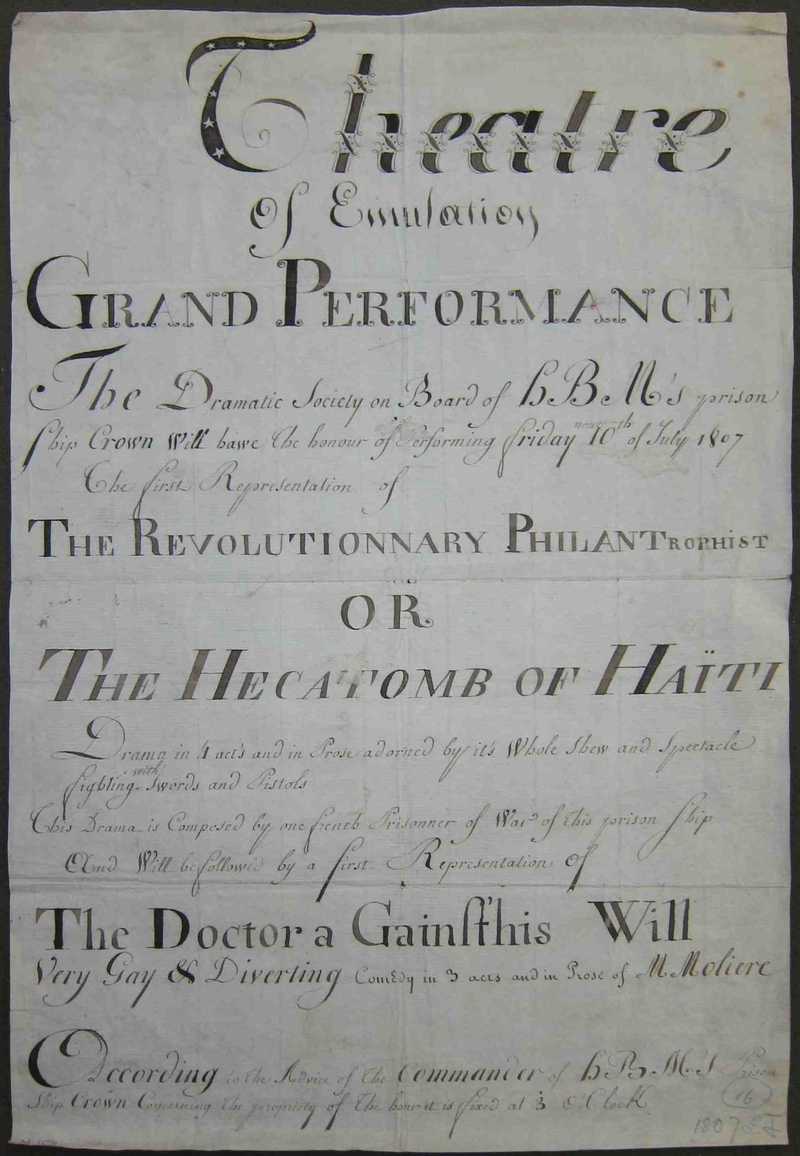

What can one learn about a performance event from a playbill, the only material trace of that event? To the scrupulous historian the answer is perhaps ‘not much’ – the playbill only proves that the performance was advertised, not performed.[1] And yet, this is not a satisfying response for those studying performance events held outside the realm of the commercial theatre, events that leave few material traces. While every performance event is ephemeral, historians of professional productions can often refer to ticket sales, memoirs of theatre practitioners, censor records, scenery and costume artifacts, theatre architecture and an array of print reviews to reconstruct those events. The playbill analyzed in this essay announces an amateur theatrical performance aboard the Crown, one of 20 de-masted naval vessels used as hulks just off the coast of Portsmouth, England during the Napoleonic Wars (Lloyd, History 84). To my knowledge this handwritten playbill, held at the National Maritime Museum, offers the only evidence of the production it announces.[2] In pursuit of a methodology that might be used to approach other unknown amateur productions, this essay theorizes the handwritten playbill as artifact.[3] As in Michael Reason’s Documentation, Disappearance, and the Representation of Live Performance, the primary intention is “to explore how we can know live performance through its representational traces” (4). Further, this analysis follows upon Jacky Bratton’s description of “intertheatrical reading” in New Readings in Theatre History, which “seeks to articulate the mesh of connections between all kinds of theatre texts, and between texts and their uses” (37), moving from the playbill to its referents: from the advertised date and venue to the history of prisoner of war hulks during the Napoleonic Wars, from the play titles to the dramatic texts they signify and from those dramatic texts to the history of the French Revolution, Napoleonic Wars and the slave insurrection in Saint-Domingue and finally to the imagined performance event. I view the playbill not only as a collection of signifiers that lead outward, but also as a rhetorical object with a role in the performance event. As such, the playbill presents data and offers a lens through which to interpret that data. Put another way, this single artifact – a promotional skeletal narrative of an anticipated event – functions as historical record and active component of the performance event.

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Performance Venue: the “Theatre of Emulation”

Theatricals were a common occurrence on the prison hulks and in the coastal towns. The name of the performance venue aboard the Crown, the “Theatre of Emulation,” can be understood as a nod toward other prisoner productions in the area. In The Arts and Crafts of Napoleonic and American Prisoners of War, Clive L. Lloyd describes theatricals as taking place during this period on hulks, in prisons on land (such as Portchester Castle) and in villages where captured French officers were held on parole (91); there are accounts, for example, of professional theatre managers outraged at the competition presented by productions at the prisons on land (284). Although the Crown playbill does not explicitly state that the “Theatre of Emulation” is located on the Crown, any other location would have required allowing prisoners off the hulk, which would invite considerable risk of escape. This supposition is supported by a better understanding of the layout of a prison hulk. In A History of Napoleonic and American Prisoners of War 1756-1816, Lloyd explains that prison hulks like the Crown were decommissioned or captured naval vessels no longer fit for sea travel. After all of the rigging and guns were removed, each was filled with over 700 prisoners and operated by a British naval complement of about 30 officers, staff and servants, and between 40 and 50 military guards and sentries (84). Lloyd describes the orlop deck, one of the lower decks still above sea-level that ran the full length of the ship with very low ceilings and minimal natural light, as a place where prisoners would sleep in hammocks at night, while during the day it was the site of a bustling marketplace of prisoner-made goods as well as lessons in fencing, mathematics and English (History 85). Given the account of activity on the orlop deck, it would seem the most likely place for a prisoner production to be mounted. Further, the playbill clearly announces a production by “The Dramatic Society on Board of hBM’s prison Ship Crown” (Theatre bill n. pag.; emphasis added).

Louis Garneray’s narrative of life as a French prisoner of war entitled Mes Pontons (with translation entitled The Floating Prison), one of the richest of such valuable memoirs available, further describes a theatrical performed on the orlop deck. Describing the hulk theatre constructed aboard the Crown, Garneray writes, “A pretty large space which had once served as a chapel lay at the end of the orlop. The floor there was lowered by several feet and the ceiling was almost twice the normal height. There we set up our stage” (145). Importantly, the orlop deck was the domain of the prisoners, meaning that British officers would enter their space for the performance instead of having the performance come to them. Richard Rose offers a revisionist history of the hulks by checking Garneray’s mid-nineteenth-century narrative against “events that can be independently checked and dated” (ix). Rose indicates the obviously invented elements in Garneray’s narrative: extended melodramatic speeches by prisoners and Garneray’s narrative position at the center of every event (xiv). Like Garneray’s French biographer Laurent Manœuvre, Rose is careful to note that “Garneray was not a simple liar or fantasist. He may have invented parts of his narrative and misplaced real names and episodes by accident or design, but he also deliberately left no records of certain events that must obviously have occurred” (xvii). Garneray seems to frame his narrative to assert French superiority; the hulk shifts from a horribly restrictive environment to a playground for clever prisoners, depending on his storytelling goals.

Garneray’s description of a hulk performance is one of many sections of Mes Pontons that adapts real events to ridicule British officers and civilians.[5] In Garneray’s account of theatricals, two captured French sailors, a midshipman and a purser, write expressly for the occasion “a farce in two acts entitled The Adventures of a Sentimental Lady” and “a five-act melodrama called The Corsair’s Sweetheart” (Garneray 145). These sailors, earning money on the hulk through straw-work and slipper-making, have such faith in their ability as playwrights that they agree to share the profits from ticket sales instead of taking a flat payment in advance (146). The performance is attended by fellow prisoners, officers from nearby hulks and ladies and trades people from town (145-47). Although Garneray describes French women as present aboard the hulk (226-28), he explains that they were so “hideous and coarse in manners and speech” that young male prisoners were made to play the female roles instead (146). This provides the necessary conditions for the amusing escape of one French prisoner. An arrogant British lieutenant, “the commander of one of the Danish hulks,” is particularly taken with the “lady” playing the female lead in The Corsair’s Sweetheart and, during one of the intermissions, pays Garneray for information about her marital status (150-51). The role is, of course, being played by a young French prisoner named Pierre Chéri, but Garneray, insulted by the British officer’s condescension, plays a trick on the inquirer. Garneray tells the lieutenant that the actress, named Clara, had begged permission to board the hulk to be with her fiancé. Her arrival on the hulk had sadly led to the dissolution of the engagement, however, since she preferred the polished look of free men. This story stirs the British officer’s desire for Clara, and Garneray negotiates their departure – arm in arm – off the prison hulk, certain that no repercussions will follow since the officer would be “too mortified to let the whole world know” (152). Instead of challenging British control through the content of the plays performed, Garneray’s narrative depicts French prisoners using theatricals to subvert British authority; however, rather than using subversive content to breed disaffection among prisoners, this theatrical quite literally enables an escape.

Although questionable as a record of a theatrical production given its obviously fictional elements, Garneray’s narrative does offer insight into hulk theatrical practices more generally. In revisions for the second edition of The Floating Prison, Rose clarifies that “in effect all the popular literature relating to the hulks, published between 1815 and 1850 is a re-hashing of a very few authors’ work, including that of Garneray” (Rose Interview n. pag.). Garneray’s account suggests that officers from other ships and civilians boarded hulks and descended to the orlop deck to attend performances without concern for their safety. It also presents theatricals as one part of the marketplace aboard a hulk since the performance was a commercial endeavor for which the playwrights, performers and orchestra (a violin and a flute) were paid for their efforts (145). Given that this playbill is handwritten and announces a performance aboard “this prison ship” (Theatre bill n. pag.), it can be considered as an advertisement directed to those aboard the Crown only; although, this does not mean that other playbills did not advertise the event more broadly. By advertising two French plays in English, the bill offers a microcosmic view of Anglo-French interaction during this period that positions French prisoners as performers for British officers. Finally, while clearly targeting a British audience, the playbill can be interpreted as advertisement or obligation; that is, it could have been posted in the interest of offering entertainment or in fulfillment of an obligation to announce planned gatherings of prisoners. Regardless, the Crown playbill sets forth an opportunity to test existing prison hulk histories such as Lloyd’s, derived primarily from memoir accounts, which often repeat as fact the memoirs of French prisoners.[6]

Dramatic Texts in Context: Le Philanthrope and Le Médecin

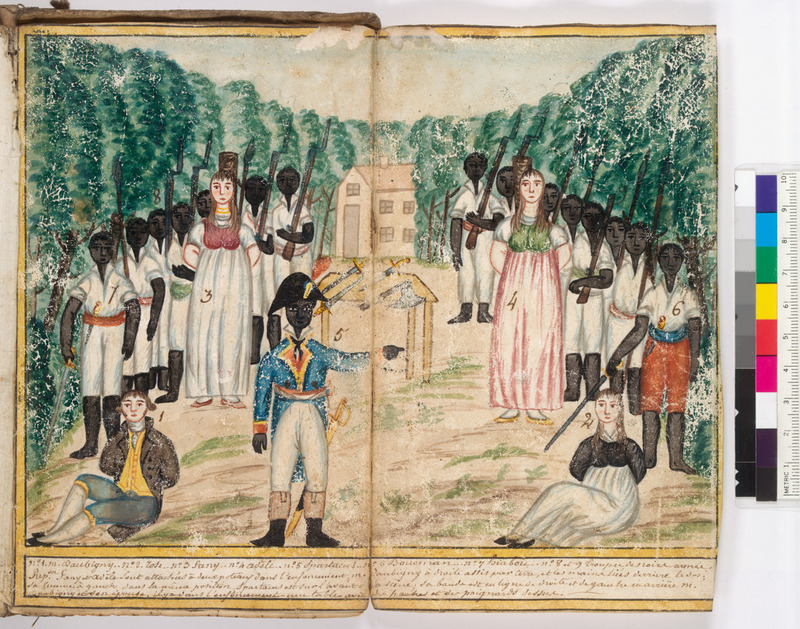

The French dramatic texts, announced in English on the Crown playbill, reflect several important aspects of the period just after the fall of the Bastille – through subject matter and production history. The playbill first announces “The Revolutionnary Philantrophist or The Hecatomb of Haïti” (Theatre bill n. pag.); the surviving manuscript of the announced play, Le Philanthrope révolutionnaire ou l’hécatombe à Haïti, depicts the slave revolts in Saint-Domingue that began in 1791, over a decade before the formation of Haiti as the first black independent republic outside Africa in 1804. The second play, “The Doctor a Gain∫t’his [sic],” or Le Médecin malgré lui, was one of Molière’s comedies particularly popular with soldiers and sailors after the fall of the Bastille (Leon 37-38). The play is composed “by one french Prisonner [sic] of War of This prison Ship” (Theatre bill n. pag.), suggesting that the anonymous author is a French sailor or soldier. The playbill’s description of the production as “The first Representation of The Revolutionnary Philantrophist” (Theatre bill n. pag.; emphasis added) might lead one to conclude that 10 July 1807 was the debut of this original play. Of course, the playbill also announces “a first Representation of The Doctor a Gain∫t’his Will” (Theatre bill n. pag .; emphasis added) even though Molière’s play dates back to the seventeenth century. As such, these firsts, when taken together, announce the production as the first of a series of performances to be given at the Theatre of Emulation. The only surviving manuscript of Le Philanthrope supports this interpretation since the cover pagestates in French, “Copied January 1, 1811 on board the hulk Crown, floating prison of Portsmouth harbour, in England” (n. pag.), suggesting that the 1807 production was the first of many productions on the Crown. This copy of Le Philanthrope could have served as a script for another production in 1811, but the six watercolor illustrations in the manuscript, depicting key tableaux from the play, suggest instead a commemorative copy attempting to capture how the play was staged.

Understanding Le Philanthrope as a historical drama requires some brief details of the slave uprising in Saint-Domingue which, for the purposes of this article, will be traced from the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. The play pivots, in fact, on the dangers that arise when French revolutionary ideals, formulated in opposition to a monarchy, are applied to the situation of slavery. Jeremy Popkin summarizes the play and translates select passages in Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection, and my reading of the play extends his project to situate it as a response to the insurrection. Unlike the autobiographical accounts forming the majority of Popkin’s collection (written by white colonists in the midst of the insurrection), this play revisits those events from a distance. Popkin explains that the colonial whites in the prosperous French colony of Saint-Domingue, long frustrated by royal trade restrictions, were enthusiastic about the French Revolution but were careful to prohibit the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen” and shut down the local branch of the Parisian Société des Amis des Noirs, a group seeking the gradual reform of slavery (6-7). White colonists were horrified by the slave uprisings that began in 1791 and despised the fiercely republican anti-Plantocracy French commissioner, Léger Félicité Sonthonax, who issued the first emancipation decree on 20 June 1793 (Popkin 245). As C.L.R. James describes in The Black Jacobins, Sonthonax was portrayed in France as “the executioner of the whites and disrupter of the colony” (180). In 1797, Toussaint Louverture forced Sonthonax out of the colony, claiming that he was planning to murder the whites in Saint-Domingue (187-90). Important here is the fact that Sonthonax – the white official – is remembered as a radical who “wanted to sweep the aristocrats off the face of the earth” (James 186).

Though fictional, Popkin includes the play in his collection because it shows “a white author trying to imagine how a black insurgent might have explained his motives and how colonial whites understood the actions of the French official Sonthonax” (245). Popkin interprets the play as a response to a play commissioned in 1796 by Sonthonax “to discredit the French antislavery faction that had opposed him during the six-month-long parliamentary inquiry ordered by the National convention in 1795” (246-47). This earlier play, entitled La Liberté générale, ou Les Colons à Paris, functions as anti-slavery propaganda, and drawing from this context, Popkin reads Le Philanthrope as “a proslavery colonist’s reply to La Liberté générale” (247). His interpretation relies on the basic elements of the plot of Le Philanthrope, which proceeds as follows: the revolutionary philanthropist, a white official, encourages the principled leader of the black insurgents, Spartacus, to take vengeance on the white, slave-holding Daubigny family. Prompted by the Philanthrope, Spartacus captures the Daubigny family and says he will spare them only in exchange for sexual favours from the two captured daughters. Monsieur Daubigny refuses and faces the wrath of the three black insurgents, but is saved just in time by three young white men, “two of whom are the lovers of the Daubigny daughters” (Popkin 247), who have been notified of the danger facing the Daubignys from a young black slave. In Popkin’s reading, the play’s sympathetic portrait of slave-holding whites as innocent victims of vengeful white abolitionists is reinforced at the end of the play when Monsieur Daubigny emancipates the young slave who contributed to their rescue.

Without the playbill, Popkin interprets the author of the play as a French colonist, but the existence of the playbill, announcing a particular production in 1807 and the author as a prisoner of war, adds new possibilities to the playwright’s identity. The playwright, for example, could have been a member of the Plantocracy in Saint-Domingue who was exiled at the start of the insurrection and consequently entering the French military. Alternatively, the playwright could have been a soldier serving in Saint-Domingue at the time of the insurrection. Still another possibility is that the playwright had no direct experience of Saint-Domingue but instead drew from material on the “flood of public propaganda” circulating in France in the years after the insurrection that featured the violence as “a stark, racialized confrontation between civilized whites and barbaric enemies” (Popkin 9). While not providing definitive conclusions, the additional material traces provided by the playbill, at least, open up further interpretive possibilities.

Ultimately, of course, the play itself is more valuable in reconstructing the performance event than authorial details. My reading of the play enlarges upon Popkin’s analysis by exploring the second part of the title, “l’hécatombe à Haïti,” which foregrounds the importance placed on a massacre as reparation for injustice. The title suggests a “hecatombe,” defined as a sacrifice or massacre, at Haiti.[7] The final lines of the play indicate that this massacre was a goal of the philanthropist and that it was not achieved in the play – there is no on-stage sacrifice of human lives. Monsieur Daubigny’s final line in the play expresses happiness at not having contributed to revolutionary philanthropy (“heureux de n’avoir pas servì d’hécatombe de la Philanthropie révoluntionnaire” [Le Philanthrope 72]), which makes the revolutionary philanthropist a spokesperson for a concept that demands the sacrificial element of the massacre of white slave owners be recognized in the cause of liberty. Notably, black insurgents are the executors of this philanthropic project prompted by white abolitionists. The revolutionary philanthropist’s desire for this massacre deepens the reading of the revolutionary philanthropist as Sonthonax, who differed with Louverture on precisely this issue according to popular accounts at the time. The reason for the conflict between the two leaders, in cultural memory at least (and this is what matters here), is that Sonthonax was too inspired by the ideals of the French revolution. The problem of the play, in other words, is that revolutionary violence becomes an end in itself instead of a means to liberty. In fact, in the logic of the play, the rhetoric of liberty serves as the means to vengeful violence: the philanthropist uses the rhetoric of liberty to propel Spartacus into vengeance. What Popkin interprets as a defense of white slave holders works by revealing an abolitionist’s vendetta against the aristocracy.

While the historical events in Le Philanthrope gesture back to the slave insurrection in Saint-Domingue, the production history of Molière’s Le Médecin conjures memories of the play’s popularity in France just after the French Revolution. In her book, Molière, the French Revolution, and the Theatrical Afterlife, Mechele Leon describes the popularity of this play after the Revolution. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the play was considered a crowd-pleaser, suitable to draw the unenlightened to the theatres. Though it was dismissed by the elite of the Old Regime, during the French Revolution, it’s popularity exceeded that of plays like Tartuffe and Le Misanthrope.[8] However, in Paris, without this elite theatre audience, broad comedies like Le Médecin were adapted – to the delight of the uneducated masses, which included soldiers (Leon 37-38) – and acted by fairground, boulevard and amateur performers. Just as it would have been popular with soldiers and sailors in France in the years after the Revolution, Le Médecin would would have had considerable appeal for these same groups when they were held as prisoners of war, particularly when one considers that this dramatic society was not a society of officers but common soldiers. While Le Philanthrope seems to invite members of the audience to consider the contradictory nature of revolutionary ideals, Le Médecin invites them to remember a familiar play.

Molière’s play, Le Médecin, makes physical violence comedic, includes an escape and is embellished with sexually explicit humour. The premise of the play is that a woman named Martine, in order to avenge the beating she has been given by her husband Sganerelle, tells two men in search of a doctor that her husband, who is actually a woodcutter, is a brilliant doctor but will only help them if he is beaten. The two men have been sent by the wealthy landowner Geronte who is desperate to find a way to cure his daughter’s recent lapse into muteness. Sganarelle is delivered to Geronte’s house where his faux medical knowledge is admired to great comic effect. Inadvertently, Sganarelle learns the real reason for the daughter’s dumbness: her father has chosen a wealthy man for her to marry, but she is in love with Leandre. Sganarelle facilitates the farcical escape of the two lovers and faces Geronte’s wrath until the lovers return to announce that Leandre has inherited a fortune and would like to request again Geronte’s consent for their marriage, which he grants. The play ends with the comical threat of abuse that initiated it, with Sganarelle warning Martine that she should fear the terrifying rage of a doctor. Though this is the plot conveyed by the dramatic text, it is important to remember that most performances of Molière after the Revolution were loose adaptations, to the dismay of French theatre critics. To return to the dramatic text referenced by the playbill, then, only allows us to speculate on the crowd-pleasing possibilities of its performance as adapted aboard the Crown.

The Politics of Performance

As captured French officers were rarely held on the hulks, the dramatic society producing the performance on the Crown was likely made up of ordinary sailors and soldiers – not officers – in the French military.[9] To understand how the plays described above invited soldiers and sailors in the service of Napoleon’s Empire in 1807 to reflect on the tumultuous years just after the fall of the Bastille in 1789 it is helpful to outline the complicated political triangle connecting England, France and Haiti in the interval between the two historical moments in question. Beyond British public opinion being fiercely divided in response to the storming of the Bastille and “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen” that followed, the British government also attempted to capitalize on the revolutionary upheaval in Saint-Domingue.[10] Toussaint Louverture famously defended French interests in the face of the British expeditionary force of 1798 only to become the enemy of France as Napoleon rose to power and sought the reinstatement of slavery at Saint-Domingue (James 200-01). By the time of this production, the British and the established republic of Haiti shared a common enemy: Napoleon. During this period of warfare, the British population was also divided over the issue of the abolition of the slave trade, debated in Parliament. This national debate was settled partially in 1807 – just four months before the Crown production – with the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade; although, slaves in British colonies were not emancipated until 1833.

With this brief historical account of the complicated political tensions and social relationships in play during the period, we can more accurately imagine the performance event aboard the Crown by using the playbill as a lens to view the venue, dramatic texts and historical context discussed in previous sections. In distributing the bill, the dramatic society aboard the prison ship offered a skeletal narrative of the anticipated event, and the structure of this narrative is revealing. The playbill announces to a British reader an event that will happen one week in the future. However, it does not explicitly state that the performance will be in French but, instead, translates the titles, adding brief descriptions so that the subject matter might be deduced. For example, the first play is presented as “The Revolutionnary Philantrophist OR The Hecatomb of Haïti Drama in 4 act’s (sic) and in Prose adorned by it’s (sic) Whole Shew (sic) and Spectacle fighting with Swords and Pistols” (Theatre bill n. pag.), marketing both the genre and the violence. Notably, the playbill devotes more attention to stage action than to description of the plot. Beyond the general emphasis on the violence depicted in the play, the playbill also suggests hostility toward the British even while it targets a British audience. For one thing, it muffles the presence of British control surrounding the production by announcing, “The Dramatic Society on Board of hBM’s prison Ship Crown Will hawe (sic) the honour of performing” (Theatre bill n. pag.). Using the passive voice, the author of this playbill avoids mentioning that this honour has been granted by any particular person, though playbills for amateur performances generally acknowledge a patron of the announced performance. That person, as the line at the very bottom of the bill notes, is the commander of the Crown: “According to the Advice of the Commander of hBM’s Prison Ship Crown Concerning the propriety of The hour it is fixed at 3 O’Clock” (Theatre bill n. pag.). Again, the language suggests that it is only with the commander’s advice not his mandate that this hour has been selected. The playbill, thus, advertises a play in which prisoners will be armed with (prop) swords and pistols, provided by a dramatic society who refuses to acknowledge their captors as patrons.

Of course, the fact that the bill translates the play titles into English foregrounds that the performance might not be completely understood by the authorities in attendance. This is a feature Garneray highlights in his account of theatricals aboard the Crown. He claims that the British women in attendance were crying in response to The Corsair’s Sweetheart but could not understand why because they did not know “a single word of French” (148).[11] As a component of the event, the playbill invites a reading of the performance that accounts for both British and French audience responses. These responses could differ in terms of interpretation and language. Of further importance to the understanding of audience response on the level of language is the distinction between the action of the play, which shows black insurgents holding white hostages, and the more complex dialogue, which reveals a white villain instigating this violence by manipulating the righteous indignation of an enslaved black man. The illustrated stage directions of the play (included below) reveal this disparity, as the Philanthrope is not pictured in the tableaux depicting the threat of violence. When performed in French, presumably staged according to these illustrations, the British spectators would see a conventionally acceptable depiction of the black character Spartacus ordering his second in command to hold a sword to the neck of a Daubigny daughter, while the dialogue would give this visual villain powerful rhetoric expressing freedom from oppression, inspired by the rhetoric of the revolutionary philanthropist.

© The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, US

This contrast between stage action or generic conventions and the political dimensions of the play’s dialogue is most apparent toward the end of the play when the violence and rhetoric are at their heights. While Spartacus holds the Daubigny family hostage, the Philanthrope encourages him to seek vengeance, declaring that he and his fellow insurgents are “free of all servitude,” emphasizing that they are “French citizens”(Popkin 250). The playwright gives Spartacus a hymn in response to this verbal liberation:

Friends, France summons us

To the joy of independence.

Woe to he who hesitates,

Be valiant, be faithful,

Let your hearts be filled with hope;

Be models

for the French. …

Don’t fear those vile whites;

They are proscribed in their own country.

We are its children;

We are born free

Of the chains of tyranny.

Oh! Let all tyrants perish! (qtd in Popkin 250-51)

The language here is the language of French patriotism against those vile whites, potentially interpreted by French prisoners as the British, while what is shown on stage is a black revolutionary threatening to kill a French family. Returning to Popkin’s suggestion that the revolutionary philanthropist is based on Sonthonax, this hymn has further resonance. According to James, Sonthonax held many demonstrations during his service in Saint-Domingue, making “the children in the schools spend many hours singing revolutionary hymns” (186). For those in the audience familiar with the French assessment of Sonthonax, Spartacus’ speech might seem like the childishly borrowed language of republican propaganda. However, this tone does not come across in the action, where Spartacus models the violent executor of vengeance. The culminating action of the play occurs just after this speech by Spartacus. The stage directions describe the following action: the second chief of the slave rebellion, Boucman, is about to deal Daubigny a murderous blow when the three white heroes appear and leap on the leaders of the rebellion. During the struggle the young slave cuts the rope that binds his master, and together, the master and the three heroes chase the leaders of the rebellion off stage. They are not seen again; the black and white villains in the play remain an off-stage threat.

This possibility of a separate experience for Anglophone and Francophone members of the audience can be understood as a coded way for the French prisoners to express their indignation against the British keepers. With attention to the live production, the moments in the play when Spartacus speaks the language of liberty, modeled on the language of the revolutionary philanthropist, become fairly complex. Though it would certainly not be the first time that literal slavery functioned metaphorically to describe conflicts between free men, the live performance has the potential to create differing visual and auditory symbols. For example, an English-speaker experiencing the live performance might not perceive the primary conflict of the written text – the white philanthropist’s instigation of the slave rebellion. Instead, he may interpret Spartacus as the primary executor of vengeance on the Daubigny family. Evident from the image above, the white philanthropist is not pictured in the tableaux depicting the threats on the Daubigny family. Furthermore, while the Revolutionary Philanthropist is motivated by ideals from the French uprising against monarchy, in performance the French prisoners might identify with Spartacus’ failed attempt at slave insurrection, given their own imprisonment. However, prisoners with sympathy for the exiled white Plantocracy might identify with the captured Daubigny family. Most importantly, by depicting the events of the slave insurrection in Saint-Domingue, the French playwright avoids pitting French heroes against British villains. In other words, the leaders of the slave rebellion and the French radical philanthropist combine to provide a safe intermediary – a complex common villain – for both French and British members of the shipboard audience.

Similarly, as escape attempts were frequent (with violent reprimand from armed sentries a sure consequence) on prison hulks, the prisoners’ performance of Le Médecin becomes an extremely relevant commentary on day-to-day life aboard the Crown, despite the obviously comedic effects. In the play, for example, characters are beaten but stand up the next moment to deliver comical rebukes; further, they execute an escape without the deadly consequences prisoners in the audience would likely meet, should they attempt a real escape. This element of absconding from detention or punishment could be made even more entertaining if the play had been liberally adapted, as it was in Parisian theatres after the Revolution. Topical jokes could easily be inserted into the dialogue of the play, offering caricatures of fellow prisoners or officers for the audience’s amusement. Add to this the physical humor and the fact that the performance would likely have been cast entirely by men, and this play seems a perfect opportunity for prisoners to (momentarily) forget their horrible circumstances to enjoy the obscene and the farcical.

Conclusion: Material Traces and Transnational Networks

The existence of the Crown playbill prompts many questions, and some remain unanswered even after this analysis: What inspired the dramatic society aboard the Crown and who were the members? Was this the only performance given by this dramatic society? Who was invited to this event? Following Bratton’s lead, this analysis has extended beyond the facts relayed by material traces to an interpretation of these traces as signifiers, which have meaning “only as part of a system of relationships” (39). Theatre historians have often approached playbills as artifacts, presenting information to be catalogued, but Bratton argues that the playbill also offers evidence “for those most difficult and evanescent aspects of theatre history – the expectations and disposition of the audience, their personal experience of the theatre” (39). Following her call to intertheatrical reading, which takes into account audience memory and generic expectations, this article explores a multiplicity of factors, including the experiences of French prisoners and British officers aboard the Crown, French soldiers and sailors attending performances of Molière after the fall of the Bastille, French citizens witnessing slave uprisings in the French colony of Saint-Domingue and British citizens following abolition legislation in Parliament.[12] Then, to imagine the performance event necessitates movement away from the particular performance event to the texts offering traces of peripheral events likely influencing the production aboard the Crown. Of course, these peripheral events are also ephemeral and reconstructed through traces – albeit more plentiful ones. Texts offering such traces include prisoner-of-war memoirs, French theatre reviews critical of the popular appropriation of Molière after the Revolution and eyewitness accounts of the Haitian insurrection. These texts do not offer objective reports but can be read alongside and against the primary artifact. Unlike Bratton’s analysis of professional British theatre practices during the height of reforms in the 1830s, which uses the playbill as a means to revising existing history, this article features the playbill as the sole material trace to constitute a history by using it as a source of information and a lens through which to understand that information. Notably, this analysis of the only material trace of a performance event has revealed the likelihood of many other performance events that left similar traces which, however scanty, can usefully further or at least complicate existing histories of the English hulks during the Napoleonic Wars and our understanding of the circulation of ideas across national, cultural and linguistic borders via performance (and print) in this period. These performances by unknown actors in makeshift venues have much to tell us about the diverse responses to revolution and empire, responses inaccessible through the published writings of well-known thinkers and the recorded performances in professional theatres.

Works Cited

Bratton, Jacky. New Readings in Theatre History. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Garneray, Louis Ambroise. The Floating Prison. Trans. Richard Rose. London: Conway Maritime P, 2003. Print.

Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Print.

“hecatombe.” Le Petit Robert 1: Dictionnaire Alphabétique et Analogique de le Langue Française. Paul Robert, Alain Rey, Josette Rey-Debove. Paris: Le Robert, 1991. Print.

James, C. L. R. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1989. Print.

Le Philanthrope révolutionnaire ou l’hécatombe àHaïti. MS 2004/247 z. Bancroft Library, Berkeley, CA. Print.

Leon, Mechele. Molière, the French Revolution, and the Theatrical Afterlife. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 2009. Print.

Lloyd, Clive L. A History of Napoleonic and American Prisoners of War 1756-1816. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007. Print.

---. “The Entertainers.” The Arts and Crafts of Napoleonic and American Prisoners of War 1756-1816. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007. Print.

Molière. The Doctor in Spite of Himself and Bourgeois Gentleman. Trans. Albert Bermel. New York: Theatre Book Publishers, 1987. Print.

Popkin, Jeremy D. Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007. Print.

Reason, Matthew. Documentation, Disappearance and the Representation of Live Performance. Palgrave: Basingstoke, 2006. Print.

Rose, Richard. E-mail Interview. 9 Nov 2010.

---. “Foreword.” The Floating Prison. London: Conway Maritime Press, 2003. Print.

Rosenfeld, Sybil. Temples of Thespis: Some Private Theatres and Theatricals in England and Wales, 1700-1820. London: Society for Theatre Research, 1978. Print.

Theatres of War: Performance, Politics, and Society 1793-1815. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1995. Print.

Theatre bill for HM prison ship CROWN. 1807. MS THP/1. The National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, Eng. Print.

Bio

Mary Isbell is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Connecticut. Her dissertation constructs a transatlantic cultural history of amateur theatricals in the long nineteenth century, drawing on archival artifacts such as playbills for theatre performances. She is co-editor, with Judith Hawley, of the forthcoming special issue of Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film entitled “Amateur Theatre Studies.”

[1] In describing the underutilization of playbills by theatre historians, Bratton writes: “The most scrupulous historians remind us that the plays advertised did not always happen” (39).

[2] Amateur productions were often reviewed in local papers; although, surviving newspapers printed in Portsmouth during the Napoleonic Wars are rare.

[3] Productions qualifying as amateur theatricals include private theatricals given by and for the aristocracy, home theatricals, performances given by university dramatic societies, benefit productions in rented theatres, shipboard theatricals and prisoner theatricals.

[4] Theatre of Emulation Grand Performance The Dramatic Society on Board of hBM’s prison Ship Crown Will hawe the honour of Performing Friday next 10th of July 1807 The first Representation of The Revolutionnary Philantrophist OR The Hecatomb of HaÏti Drama in 4 act’s and in Prose adorned by it’s Whole Shew and Spectacle with fighting Swords and Pistols The Drama is Composed by one french Prisonner of War of This prison Ship And Will be followed by a first Representation of The Doctor a Gain∫t’his Will Very Gay & Diverting Comedy in 3 acts and in Prose of M Moliere According to the Advice of the Commander of hBM’s Prison Ship Crown Concerning the propriety of The hour, it is fixed at 3 O’Clock

[5] Narratives of amateur performance serve the same purpose for nineteenth-century novelists, though the choice of social class being ridiculed varies. Consider Mr. Rushworth in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814) and Mr. Wopsle in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations (1860-61).

[6] Francis Abell’s Prisoners of War in Britain 1756-1815 (1914) offers one example of these histories.

[7] The term “hecatombe” is defined in Le Petit Robert 1 first as a sacrifice and second as “a massacre of a large number of men / persons” (massacre d’un grand nombre d’hommes), the latter being its likely usage in this play.

[8] Leon explains that just after the Revolution, the elite classes fled France en masse (38). Some of these émigrés were in England and mounting private productions of Molière themselves. Sybil Rosenfeld notes in Temples of Thespis a performance of L’Avare (The Miser) given at York House, Twickenham in 1803 (170).

[9] Rose explains that “each officer willing to give his word of honour not to escape was briefly confined until arrangements could be made to send him to one of the […] towns where such parole prisoners lived, subject to various regulation, in relative freedom and often in considerable harmony with the local inhabitants” (xi).

[10] Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) and Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) demonstrate two extremes of this reaction.

[11] The trick on the British lieutenant also pivots on Garneray serving as an interpreter and therefore could be a fictional necessity, so this need not suggest that no British members of the audience understood French.

[12] Following Bratton’s borrowing from literary studies, one might also think of the playbill as an epitext, functioning similarly to the promotional materials for a printed book theorized in Gerard Genette’s Paratexts. Unlike the emphasis on the written text driving Genette’s analysis, however, the object at the center of this relationship of literary object and mediating influences is not written, but ephemeral. The playbill mediates not the dramatic text but the performance event. This might be best understood in relation to the literary scholar’s attempt to recover the experience of reading the written text; in each case that fleeting experience is of optimal value to the historian and only interpretable through material traces.