Media X In the Interstices: emergent spaces between print and digital (or, on machinima, QR codes, and turning ten)

Jenna Ng

Part I

The whole idea of it makes me feel

like I'm coming down with something

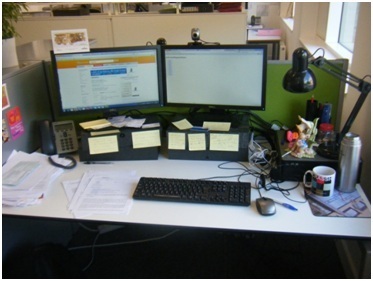

I write this article in multiple modalities: typing on my primary computer screen; referencing pdfs, websites and other digital sources on my secondary screen; shuffling papers on my desk; glancing at a corkboard on which I had pinned sketches of project ideas. I also write this in multiple moods: trepidation with the challenges of a current project; elation with the progress of an idea; thrill at the possibilities and potentialities from my work. Finally I write with multiple hopes, incubated personally and professionally: writing a new book; an imminent graduation into another age bracket; and, not least of all, the welcomed revitalisation of the humanities with digital technologies.

Author's workspace.

As I flounder through all this, I realize it is not all, as they say, in the mix, but also in the interstices. My excitement lies not only in contemplating new projects and ideas, but also in experiencing their between-ness as I move from page to corkboard, or lurch from hope to fear. I extrapolate this thought to the notion of digital projects: while digital technologies certainly introduce unprecedented possibilities for outputs – presenting information in new forms such as as digital databases, using spatialities in three-dimensional virtual worlds, acquiring new information through Geographic Information Systems or text encoding – I argue that the liminality between digital and physical realms similarly proffers emergent spaces for play and exploration. What I want to develop in the rest of this article is thus not the distinctiveness of the digital output per se, already well-discussed elsewhere, but the interactions of the digital with the physical and the spaces in which they connect, merge and co-operate. What kind of space emerges, and how may it be designed for maximum benefit and ease of use? How does one enhance the other, rather than substitute each other? The challenge, then, is to investigate these interstices of digital and textual scholarship, to see what new interactions and connections may come to light. And to see if, as I survey the multitudes of emotions, screens and reference materials before me, there might be some usefulness in zinging and zapping through the messiness and chaos, after all.

Part II

You tell me it is too early to be looking back,

but that is because you have forgotten

the perfect simplicity of being one

I soon had a chance to explore this emergent space of physical/digital between-ness. I have been working over the past year on a book project titled Understanding Machinima: essays on filmmaking in virtual worlds (London; New York: Continuum Press, 2012), an edited academic collection of fourteen essays by scholars around the world presenting different perspectives on machinima (or films made in real-time in virtual worlds), from game art to survivance of Indigenous cultures to pedagogy across disciplines. Originally conceived as a traditional print text, two issues soon presented themselves. The first is that machinima is a largely, if not wholly, digital enterprise from conception to exhibition. It is created in game worlds, such as Halo and World of Warcraft and/or social virtual worlds such as Second Life, with avatars as “actors” and virtual cameras recording in virtual sets and spaces. Editing is done on software, such as iMovie or Final Cut Pro, before the machinima piece is uploaded onto various Internet channels where it is typically viewed, commented on and shared by members of online gaming communities. Indeed, one of the charms of machinima for me is the perfection of its digital ecology spun between video games, virtual worlds, digital cinema and the World Wide Web, and the fluidity of how it transposes from one media form to another. To baldly transfer the study of it onto a printed page, straitjacketed into black text on a cream page, seemed to me a shameless robbery of its beauty and power. The second issue is more prosaic. In my home discipline of film studies, film scholars frequently describe film scenes or sequences in prose and still images, many of which are now available as online film clips. Not only is this ironic (cinema, when reduced to a palette of still images, is parsed into photography, deprived of its fundamental elements of duration and movement), but it is also clunky.

The two problems crystallized into one issue: how to bring the digital into the physical? Put this way, the issue becomes one that is more than just about machinima or film clips, but about the navigation of the digital world in research and scholarship. What if I could make a book simultaneously physical and digital, shifting between printed page and video clips, podcasts, interactive maps, hyperlinks? How may we add digital dimensions to a physical research output so as not to substitute the latter but to augment it? How can we include print texts into the fluid media ecology of the digital, rather than set them up in opposing binaries (online journals versus print journals, books versus ebooks, articles versus websites etc)? I started to turn over in my mind the possibility of creating a text which could not only organically integrate digital and physical content – “the perfect simplicity of being one” – so that one flowed to and from the other, cross-referring each other and allowing for interactivity, but which could take into account mobility and the portability of digital devices. By such integration, the physical could use the modalities of the digital to stay fluid and changeable in keeping with the latter’s immateriality, while still retaining the ease of use and reading that comes with the former.

Part III

But now I am mostly at the window

watching the late afternoon light.

The key issue lay in designing that liminal space, the conduit – as opposed to the content itself – through which digital content can be accessed easily in the physicality of the output. I considered two existing designs:

1. Directing the reader. This method directs readers of the print text to a website or a digital repository by way of a web address printed somewhere on the page. The advantage is that it is simple; the disadvantage is that it is troublesome and is neither compelling nor elegant. Typing in a web address is ponderous, and to have to move from the act of reading to typing is disruptive.

2. Accompanying media. Here, the print text is accompanied by a media storage form, for example a CD-ROM. However, there are several disadvantages. The process is cumbersome: one has to open a thick plastic case, or take it out of its plastic sleeve, insert the disk in a computer, wait for it to be read, navigate the file explorer, click on a file and wait (again) for it to launch in the hope that all the drivers are up to date for the software. The need for hardware apparatus – a drive-enabled computer or laptop – also renders the operation inflexible. Moreover, such storage technologies are fast heading for obsolescence as streaming, cloud-based apps and other mobile technologies take over. A CD-ROM can also be easily lost or misplaced. I do not see any advantages.

Instead, I decided to use Quick Response (QR) codes – two-dimensional visual structures which can be read by a digital camera in a portable device, such as a smartphone – to be this conduit. This has several advantages. Firstly, it is a relatively seamless process from page to screen: simply position the mobile device over the code and the website loads with minimal effort. Secondly, the mobility of such content is appealing, such that a chapter may be read and its digital content accessed, say, on a bus or while waiting for a friend, which would be impossible or at least very much more difficult with a CD-ROM. QR codes are also free of licenses, are clearly defined and are published as an ISO standard. The disadvantage is that one would need a camera-enabled device for this. Yet, every trend indicates that these devices are spreading fast: smartphones and tablets already exceed PC sales in 2011; an article in The Economist cites a Nielsen report that almost half of American mobile-phone subscribers last year had smartphones, “compared with under a fifth two years earlier” (2012, n. pag.). It seems myopic to reject QR codes simply because not everyone owns a smartphone at the moment when there is every indication that that will certainly change in the future.

By printing a unique QR code at the top of each chapter, every essay in the book will thus be linked to a dedicated webpage containing all the complementary digital content for it:

Since I envision this to be a mobile solution, I designed the website on the digital end to be suitable for a portable device screen, giving careful consideration to relevant modalities, namely:

- The digital material has to be able to be read and accessed comfortably within the (general) dimensions of a mobile screen;

- Colours have to be appropriate for a small screen, as with the site’s font sizes and font types;

- Empty spaces on the page have to be carefully apportioned with text so as to balance between not being over-cluttered, yet still making full use of the small screen to portray content;

- Downloading time must be taken into careful consideration, particularly with mobile devices, so the site cannot be over-laden with anything which might excessively slow down the process; and

- It has to be hosted on a stable source – in this case, Continuum’s server – as these digital materials are as vital as their respective print texts.

For these reasons, I did not use mobile templates or mobilising technologies which emit mobile pages by applying them to standard website templates. The latter option is particularly unhelpful as it simply creates a scaled-down website unsuited for small-screen viewing: screen space gets distorted, lines run over each other, and the whole process of accessing the material becomes difficult and problematic. I decided to design the website from scratch to preserve the integrity in its structure, for this book exists in both its physical pages as well as its digital content. And to make them work together and with each other, to make this text the way I want it to be – clean in design, elegant in process – I had to start from the very beginning.

Part IV

This is the beginning of sadness, I say to myself,

as I walk through the universe in my sneakers.

Digital technology is not only my personal passion, but also forms the core of my research. It is easy for me to focus time and energies on incorporating the digital in my work, and this foray into QR codes – as with, even, the hyperlinks scattered throughout this article – is part of that deal of harnessing digital technologies as creatively as I can in both life and work. I find digital technologies fun, engaging and horizon-expanding; the fact that it is also a revitalisation of an academic ethos so bogged down by tradition and rigidity does not hurt. But I am also seeing the playing of liminal spaces, such as this print-digital transition, as something more: it is also symbolic of the hope I am mining out of intransigent and uncompromising structures, such as, say, a thread-bound paper-printed text, and of a style of fluidity and ease with which we can navigate difficult paths. I have littered this article with lines from Billy Collins’s poem, “On Turning Ten”, where its protagonist – a boy approaching his tenth birthday – reflects on how he is now leaving behind his childhood as his age turns into double digits: “it is time to say good-bye to my imaginary friends, time to turn the first big number.” The poem is poignant in its solemnity of leaving behind a childhood (on numerous levels) of innocence and fantasy; growing up is indeed a very sobering reality. Yet in the crevices, in the liminal spaces, in the between-ness ways of finding other spaces to breathe and be creative – I see in them ways of mining hope. I use the digital, because of what it means to me, as my strategy for reminding myself of these ways and of these possibilities. It is a necessary reminder because, as in work, as in life, every day, we turn ten.

Bio

Jenna Ng is currently a Newton Trust/Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities (CRASSH) at the University of Cambridge, where she is writing up a book project on presence and embodiment in camera-based digital media. She is primarily interested in the cultures and theories of digital media, particularly in relation to imaging technologies such as digital video, virtual cinematography and motion capture, but has also written on other topics such as cinephilia, cinema and time and East Asian cinema. Besides Understanding Machinima: essays on filmmaking in virtual worlds (London, New York: Continuum Press, 2012), she has also published work in various essay collections and journals, including Screening the Past, Rouge and Cinema Journal. Her website can be found at http://knittedgardens.net.